Meia Volta #5: An Amazonian Accordion, Owerá's Native Rap, and a List for Grieving Carnaval Lovers

Painting a Fuller Picture of Brazilian Music

Oi, Brazilian music lovers <3

Co-editors Beatriz Miranda and Ted Somerville here, and we are pleased to present you to Meia Volta’s Issue #5!

In this issue…

Q&A with guarani rapper Owerá; a Brazilian music podcast you gotta know; an Amazonian story of a passionate accordionist through the lenses of an award-winning photojournalist, and more!

Bora lá? :)

“Music comes as a purpose of gratitude”

Exclusive Q&A with Owerá.

For those who, fallaciously and racistly, insist on associating Indigenous culture with the past, Owerá, a Guarani Mbyá musician, comes to prove the radical opposite: He blends the tradition of his people with the newness, tune, and fast pace of a 24-year-old Gen Zer. Born and living in Krukutu (a Guarani village located right next to the São Paulo megalopolis), Owerá uses hip-hop (or native rap, in his own words) to purvey a message of change, resistance, and respect for nature and the long-threatened Indigenous rights. Below is an edited version of our conversation:

MV - Last February 10th, you paraded with Vai-Vai, a samba school in São Paulo, which spoke about the hip-hop culture in that city. What was it like for you to have participated in the samba school universe representing the Guarani people?

O - It was a new experience for me, parading and representing my culture. There were other Guarani relatives there, which made me feel more secure about participating - it wasn't just one Indigenous person. I was happy that they remembered me as a reference in rap music and that I was carrying this message as an Indigenous person, who represents Indigenous peoples. It was an experience that, if I have the opportunity to go again, I will definitely go. And I would like to take more of my people.

MV - We talked for the first time four years ago. What has changed in these four years in your professional life, and in the way you understand yourself as an artist?

O - I started singing in 2014. At the end of 2014, I started making Guarani rap. It was a learning experience. To this day, I am discovering new techniques in music, and today, ten years later, a lot has changed. In the way of writing, reading, and adapting music. I am learning more about the struggle of the Indigenous peoples too. And when I was little, I didn't know how to speak Portuguese. I learned when I was ten years old. At that time, I didn't understand what people were saying in the city. I also couldn't say what I thought or what I wanted. Today, I mix the two languages, Guarani and Portuguese.

About where I am at the moment in the music scene: to be honest, I never imagined that my rap and my musical works would reach several places in Brazil, in several states, and even outside of Brazil. When I see my music, children singing in other villages in Brazil, I feel very happy. And it is also because we know that many young people are inspired by listening to our music, which is the most important thing - raising awareness among the people of the city and raising awareness among young people in the villages in order to strengthen Indigenous culture further.

Meia Volta - When did you start to bring the Portuguese language into your compositions?

O - When I started rapping, I did it in Portuguese. I hadn't yet researched what the rhyme could be in Guarani, it was a little more complicated, but I studied it. I started listening to Brazilian rap, which is why I started making my first rap songs in the Portuguese language. And when I started rapping in Guarani, I enjoyed it a lot. It's my first language. I find it easier to sing, and I can speak more clearly, with strength in my voice and throat. But I also strive to write well in Portuguese. And being able to translate correctly from Guarani to Portuguese.

In Portuguese, since there are more words, I have to be more careful, right? I Google what some words mean, because I don't speak it all the time. Here in the village we only speak Guarani. I research every word I speak in Portuguese so as not to convey the wrong message.

MV - What was your first contact with rap and hip-hop culture?

O - First it was with my brother. He really likes rap and other musical styles. But I stuck more to rap, the style that I loved. He showed me the songs by Racionais MC's, and I started looking into it more.

MV - You talk a lot about your music as native rap, right? How do you define native rap?

O - So, when I sing in my language, I make native rap. Every rap that an Indigenous person makes about their language, about their culture, food, tradition, becomes the native rap of that ethnic group.

MV - What are your first memories in life linked to music?

O - I'm going to talk a little about Guarani spirituality. We believe that a baby already came to Earth knowing the Guarani songs. Babies arrive bringing the song of the ancestors, which connects us with Earth beings, spiritual beings, and forest beings. This would be a purpose given by Nhanderu, who is our God, to the babies, before they are born. When the child is born, the prayers and songs that we have today in Guarani culture are also born. Music comes, through children, also as a purpose of gratitude. It's for us to remember why we are walking on this Earth. And to carry our prayers forward.

When I started rapping, I decided to write poetry too, because my father was a writer. I already listened to rap, and I started transforming these poems I had written into rap. I found a flow, a rhythm. After I did my rap, I called my brothers and sang for them, who were my first audience. A year after I started, I managed to give my first performance in Diadema. It was in 2015.

MV - And tell me what the construction process was like for your last album, “Mbaraeté”?

O - I am very happy to have made this album, where I called on other artists who I already admired. The Brô MC's, who are the first indigenous rap group in Brazil. Djuena Tikuna, who sings a lot about spirituality and nature. The album starts with an introduction that I decided to call “IntrOwerá.” And that sums up everything I'm going to talk about - that I'm coming to raise awareness, bring the force of nature, show different languages. And show the true story of Brazil that has not been told.

‘Mbaraeté’, the album's name, means “Resistance”. The album talks about nature, but also about politics.

MV - On which fronts did you participate in this album’s construction process?

O - When I started, ten years ago, I just wrote the lyrics, took the instrumentals from the internet, and sang over them. And I looked for producers who wanted to support and get to know our music, because it was very difficult to make all the instrumentals with quality, and also the vocal recording. ‘Mbaraeté’ is the first project that I did, back in 2019. To make this album, I took everything I had already learned. Even to make the music videos.

MV - Talking of which, the clip that caught my attention the most, that I was mesmerized by, is that animation with a child and a giant frog. It feels like we are inside one’s dream.

O - That’s Jaguatá Tenondé. That’s my son there. Jaguatá Tenondé means “Moving Forward”. And I sing that song together with my partner, Pará, and my niece, Maitê... We sing verses about Nhanderu, our Guarani God, who came to illuminate our journey.

***

ON THAT NOTE…

On the night of February 11th, Salgueiro Samba School took a stand for Indigenous rights, raising a red flag for the Yanomami people under the spotlights of Rio’s world-famous carnival parade.

The Yanomami gained international visibility after February 2023, when newspapers denounced the devastating effects of longstanding illegal mining inside the Yanomami land - including sexual violence, diseases, malnutrition, murders, deforestation, and water contamination.

Salgueiro’s competing song, “Hutukara” - meaning “Earth” in one of the six Yanomami languages - exposed the violence against the Yanomami while criticizing the attitudes of the non-Indigenous Brazilian society.

“You don’t even know my name, and laughed at me starving when fear tore me apart/ You want to hear me singing in “Yanomami” to post on your social media profile (...),” says the scathing lyrics, whose catchy chorus line says “Ya Temi Xoa!” - a Yanomami expression meaning “I’m still alive.”

BRAZILIAN MUSIC IN A PHOTO

The guest contributor of today’s “Brazilian Music in a Photo” is Raphael Alves.

Alves is an award-winning photojournalist based in Manaus. He is a contributing member of the Everyday Brasil project.

“I was in Boa Vista, Roraima, covering the crisis the Yanomami people are going through. I stopped next to the market, where there were several homeless Yanomamis. I was with my friend and fellow photographer, Michael Dantas. After the work was done, when we were returning to our vehicle, we heard an accordion sound. We looked, and there was a truck parked on the street, and through the windshield, we saw the instrument being played. We approached and talked to the person who made it resonate. It was Mr. Aristides da Sanfona (Aristides The Accordionist). He works on a truck supplying stallholders, but his true passion is music. He told us about his life, about the regions of Brazil (all of them) where he had taken his accordion. He currently lives in Boa Vista, but he doesn't know until when: he is always willing to travel. He blessed us with some songs with his deep voice and agile hands and said goodbye. It was time to head on his way.”

LIST: BRAZILIAN SONGS FOR GRIEVING CARNAVAL LOVERS

Yup, Carnaval season is officially over.

In Brazil, Carnaval is foundational to our culture - so much so that folks joke that a year only “starts” when this festive season comes to an end. For all of those grieving for Carnaval 2024 - and already counting the days until Carnaval 2025 - here is a list of carnival-related songs (old and new, melancholic and fun, originals and cover versions) for you to dig into. Enjoy!

Marcha da Quarta-feira de Cinzas - Nara Leão

Risos e Lágrimas - Clara Nunes

As Pastorinhas - Nelson Gonçalves

Bandeira Branca - Dalva de Oliveira

Enredo do Meu Samba - Jorge Aragão e Sandra de Sá

Noite dos Mascarados - Chico Buarque e Maria Bethânia

Banzeiro - Dona Onete

Touradas em Madrid - Emilinha Borba e João Goulart

Mama Eu Quero - Carmen Miranda

Tic, Tic, Tac - Carrapicho

Feijão de Corda - Daniela Mercury

Início de Felicidade - Roberto Ribeiro

Quero um Carnaval - Júlio Secchin

Manha de Carnaval - Elizeth Cardoso

A Luz de Tieta - Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa, Banda Didá

Margarida Perfumada - Timbalada

Maracatu Atômico - Nação Zumbi

Arreda do Caminho - Maracatu Leão Coroado

Maracatu Embolado - Bangalafumenga

Brilho e Beleza - Muzenza

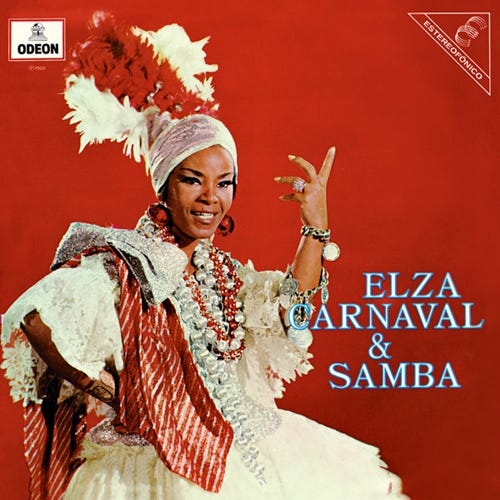

Rio, Carnaval dos Carnavais - Elza Soares

BRAZILIAN MUSIC INITIATIVE YOU GOTTA KNOW: BRAZUCA SOUNDS

Brazuca Sounds is an English-language podcast about Brazilian music founded by Leandro Vignoli.

Vignoli is a Brazilian journalist who worked as a radio broadcaster for years. He currently lives in Toronto, Canada, and often writes in the third person just to make Tim Maia proud.

MEIA VOLTA - How did you come up with Brazuca Sounds?

LEANDRO VIGNOLI - I realized there are a lot of Brazilian music fans and record collectors, but not much information is available about the context and culture surrounding that music and its artists. Other than my passion for music (in general), and talking about, and discovering new stuff every day, it was also a way to connect to Brazil as I've been living abroad for so long.

MV - What fascinates you the most about Brazilian music?

LV - The variety of different genres, sounds, and even locations, especially when it's all blended to a degree that becomes so distinctive. I've always been mostly attracted to sounds rather than words, but the more I paid attention to lyrics, the more amazed I've become at it all.

“I realized there are a lot of Brazilian music fans and record collectors, but not much information is available about the context and culture surrounding that music and its artists” - Leandro Vignoli.

MV - What do you think foreign audiences should know about Brazilian music?

LV - That is so vast and fluidly mixed to a point that a dude can sing about Jesus Christ, Afro-diasporic religions, and alchemy in the same record, and that not only is fine and acceptable, but it has become one of the greatest Brazilian albums ever produced.

MV - What are you listening to now?

LV - I'm guilty as I mostly talk about the 1970s on the podcast, so I've been endlessly listening to Cartola (why not, eh?). From contemporary musicians, I love Rodrigo Campos' latest work, both his solo album "Pagode Novo" and his duo with Rômulo Froes "Elefante". Amaro Freitas' singles are just as beautiful as expected, and I'm so looking forward to listening to his full album.

***

Thanks for reading us, and… see you soon for Issue #6 😍