Meia Volta #9: Gabriel da Muda's Path Into Samba, an Improvised Percussion Set in the Amazon, and Choro Day

Painting a Fuller Picture of Brazilian Music

Oi oi!

Beatriz Miranda and Ted Somerville here. How’s it going? How did you like Issue #8?

We are thrilled to present you Issue #9 of Meia Volta, the first newsletter to bring the nuances of Brazilian music they don’t tell you about 👌

In this issue…

The Brazilian song Maria Preu can’t live without; Gabriel da Muda talks about samba, fado, and composing; Choro National Day, Anitta’s latest album, and more!

Bora lá? :)

BRAZILIAN SONG OF MY LIFE

Maria Preu is a self-taught singer, composer, and guitarist. Born in Bahia, she has performed at Piano-Bar Fino da Bossa, Casa das Rosas, and at Memorial da América Latina to a crowd of 50,000 people.

“When my mother was pregnant, she always listened to the singer Adriana Calcanhotto. I grew up listening to her, especially the album ‘Perfil’ on CD, and I really love all of her songs. In the middle of the pandemic, I discovered myself as a singer, and Adriana became one of my choices as a Brazilian artist to study. Adriana emanates a sense of calmness when singing and playing the guitar, and serves as a reference for several generations.

I’ve picked “Devolva-Me” (Give Me Back) because it reminds me of many sweet moments when I was a child singing the melody with my ‘mainha’ (my mom). “Rasgue as minhas cartas e não me procure mais…” (Tear up my letters and don't look for me anymore), and trying to sing on note. Such good memories!”.

BRAZILIAN MUSIC IN A PHOTO

Michael Dantas, a photojournalist for over 15 years based in Manaus, works for the main media outlets in the northern region of Brazil and collaborates with international news agencies, such as Agence France-Presse (AFP) and Reuters.

“I took this photo of musician Leonardo Pimentel in September 2023 during the historic drought of the Amazon rivers. Leonardo created an improvised percussion set using the trash that appears at this time of year due to the drought in the Rio Negro. He lives close to Igarapé do Educandos, a tributary of the Rio Negro. In 2015, he realized that all that junk there could produce sounds, and he started going to the place to make music, transforming his art into a protest against all that trash at low tide.”

Leonardo is a percussionist in the Amazonas Filarmônica.

“Samba is a State of Mind”

Q&A with Gabriel da Muda

Beyond an artistic surname, “Muda” is a region of Rio’s neighborhood Tijuca, where Gabriel da Muda and his music formation flourished. In Tijuca, Gabriel grew up as a lead singer in his school choir and a self-taught player of cavaquinho. There, he also met his neighbors and nationally acknowledged composers Aldir Blanc and Moacyr Luz. Thanks to the latter, Gabriel deepened his passion for samba and helped found Samba do Trabalhador, a “roda de samba” (samba circle) that changed the contemporary samba movement in Brazil. A singer, instrumentalist, and composer, “Da Muda” spoke to Meia Volta about the meaning of samba in his life, the music connection between Brazil and Japan, his passion for Portuguese fado, and the release of his latest album.

Check an edited version of our interview below:

Meia Volta - What are your first life memories related to music?

Gabriel da Muda - My mother always had a relationship with Brazilian music, but nothing that really justified my involvement with music. My father plays a little guitar, and I play guitar, but not Brazilian music.

I think my first contact with music was when I was around ten years old. I had a cavaquinho and I learned some choros on my own from newsstand magazines. When I was twelve, I joined the school choir. This involvement with the choir was very important to me. To give you an idea, at the age of twelve, I was already the lead singer in the choir. It's crazy, but when I was around twelve, or thirteen years old, I already had a musical agenda, and I was committed to music. This encouraged me more and more and made me understand that music was really my path.

MV - Did you choose the cavaquinho? Was it a spontaneous, almost “naive” choice or was there a special reason why you chose the cavaquinho at the age of ten?

GM - No, it was definitely a naive choice, in quotes. I even like that, “naive choice”, because I had never stopped to think about it that way. Or because I thought the cavaquinho had more of a connection with samba, which is actually nonsense: the guitar is absolutely also a samba instrument. Maybe I could naively think that cavaquinho is more exclusive to samba.

MV—Do you think growing up in Muda (in the Tijuca region) and living in that region of Rio influenced your approach to samba?

GM - Tijuca had a huge influence on my musical education. It is historically a very musical neighborhood. Several big things happened in Tijuca. But, besides that, I've always been enchanted with Tijuca, you know? And Tijuca is where I met these two incredible figures, Moacyr Luz and Aldir Blanc (two of the greatest MPB composers from Rio), who are, I'd say, neighborhood bards.

MV - How do you see the Samba do Trabalhador (The Worker’s Samba) movement and its importance for preserving Rio's samba circle culture?

GM - I joke that I left home to eat ribs and potatoes and have a beer, and ended up becoming the founder of one of the most traditional circles in Rio de Janeiro. I'm not going to say that I consider Samba do Trabalhador a miracle because there's a lot of work behind this story. But I can't imagine a samba circle appearing today, that covers entry, and that fills up like Samba do Trabalhador. It dates back to 2005, a pre-internet moment. Nowadays, the internet has shortened this path of transforming a simple project into an ultra-hyped project. I think having a composer like Moacyr - I don't think he even saw himself as a samba singer before Samba do Trabalhador, you know? - caught a lot of attention. And not to mention, of course, the thing about samba being on a Monday. We have always had the idea of giving space for singers and composers to present their songs. So we've seen a lot of music emerging there. All of this contributed to Samba do Trabalhador becoming this samba circle reference.

MV - I’d like to hear more about your creative musical process. Is there anything that inspires you in this moment of playing and singing? What’s behind your composition process?

GM - Well, my composition process is still very discreet, very shy. I have some songs already recorded, and one will appear on the new Samba do Trabalhador album. I really like the melodic lines of Mauro Duarte and Paulo César Pinheiro - who, in addition to being great lyricists, are great melodists. Dona Ivone Lara, Luciana Rabello, and Mauricio Carrilho as well, who are are also great composers. I always go along that line, you know? I really like simplicity. And, as a singer, I always look for many references beyond samba. I really like Nana Caymmi, I'm in love with Dorival Caymmi. Dorival is my favorite composer of all. I listen to a lot of fado, too. When I sing in the samba circle, you will definitely see some fado nuances there, because I am passionate about fado singers. My singing is a combination of all my references in music.

MV - And now, regarding your latest album - ‘Se For, Me Chama’ (If You’re Going, Let Me Know) - what guided, aesthetically and semantically, your choices - of which songs, composers, instrumentalists would appear on the album? Did you think of a narrative, a story you wanted to tell?

GM - Those were very intense years with Samba do Trabalhador. I think I was too focused on that. And in 2020, at the end of 2019, I’d already organized to start recording my other album, but the pandemic came. And in 2023, I said, “Man, I'm going to get this project off the ground anyway.” It's a process that took, and I say this with calm, at least ten years. I've always been very careful with my repertoire. There are ten songs, five by Roberto Didio and partners, and five by Paulo César Pinheiro and partners.

MV—You recently returned from Japan, right? I’d really like to hear about your experience there. What was it like to play and talk about samba with the Japanese people? What did you learn? What surprised you?

GM - Japan is the first and only country I visited where when I said I was Brazilian, the first word they said was “samba.” From the waiter to the sommelier. I think that already says a lot. And I always like to highlight the role of Luciana Rabello and Maurício Carrilho in spreading Brazilian music there. They have been teaching Japanese people since the 70s. The Japanese have a lot of knowledge about our culture. Many don't even speak Portuguese, but they know how to sing perfectly any samba by Paulo César Pinheiro, any samba by Paulinho da Viola. To give you an idea, I took 25 Samba do Trabalhador records to sell there. I only sold four, because they all already had these albums. It's very beautiful and very moving. We feel very valued.

MV - Did you feel this connection with samba in several Japanese cities you visited?

GM—There's a samba group in Osaka, a samba group in Kyoto, and a group in Tokyo, it goes without saying. There's a group from Tokyo who come here every year and have a carnival group here in Rio, in the Vila Isabel neighborhood, in fact.

MV - For you, what is most fascinating about samba?

GM - I don't see samba just as a musical genre. Samba is a state of mind. In samba, everyone is equal, regardless of social occupation. Samba portrays everyday life, and I am passionate about everyday life. I'm a street watcher. I'm a carioca who likes to sit in a bar, sometimes not even to drink, just to watch what's going on, to watch the people. Samba is the voice of those who never had a voice. Samba manages to penetrate all political layers, all social layers. And it ends up involving people who are listening to it without even knowing that it is a political manifesto. I don't think any other genres in the world have managed to be that way. I refuse to say that samba is just a musical genre. Samba, for me, is everything.

BRAZILIAN MUSIC NEWS

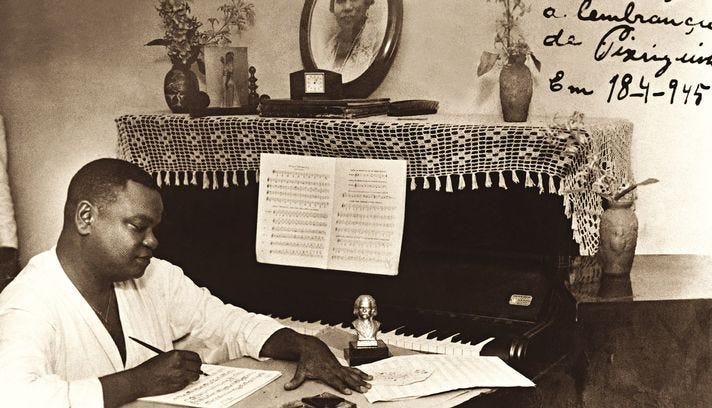

On April 23, Brazil celebrated the National Day of Choro - the Rio-born, first authentically Brazilian urban music. April 23, by the way, marks the birthday of Pixinguinha, composer, flutist, and saxophone player who incorporated aspects of jazz and Afro-Brazilian rhythms into choro music, promoting a revolution of choro with innovative arrangements. Here is a handful of fantastic tracks that belong to the choro universe - an umbrella that encompasses genres like choro-sambado, maxixe, lundu, the Brazilian waltz, among many others:

”Lundu característico”

“Gaúcho”

“Brejeiro”

And speaking of jazz (a culture strongly marked by improvisations, as much as choro music)… International Jazz Day is celebrated today, on April 30.

And you better get ready for our next issue, which will feature an exclusive interview with one of the big names from the Brazilian samba-jazz scene… 👀👀

Last but not least… Did you hear about “Funk Generation,” the latest album by Brazilian megastar Anitta? Worth listening to ;)